By Emanuel Pariser, Co-Founder and Co-Director, The Community School

Reprinted with permission from Communities magazine (Spring 2002, #114), a quarterly publication about intentional communities and cooperative living. Sample issue $6 ($7, Canada); year’s subscription, $20 ($24, Canada). send an email, visit store.ic.org, or call 540-894-5798

The white three story new england style house perched at the top of Washington Street in picturesque Camden, Maine is home to the Community School, an integral part of this small, coastal town. Renowned for its beauty and prosperity, Camden may not appear to be the most likely home for Maine’s oldest alternative school. Yet since 1973 the Community School has been helping high-risk teenagers restore their confidence and complete their high school education, gaining support yearly from the area’s residents, businesses, and organizations.

If you climbed the hill to visit our School you might find one of the co-directors talking by phone to a graduate now in his third year of college in Hawaii, working on a pre-law degree and doing well. The last time this student was in a public high school he upended his principal’s desk on him in a rage over being suspended. Like others, this young man had to work hard (it took him 14 months) on the application challenges we gave him before he could become a student here. At the dining room table you might meet a 33-year-old alumni who dropped out of the School in 1985. He has returned to take classes and complete what he started more than a decade and a half ago. In the living room you might see a group of young women enrolled in Passages, our home-based program for teen parents, taking a workshop on first aid.

What we call “Relational Education”–relationships and a sense of community–forms the context for learning at the Community School. And it works. For students who have attended the School for two months or more, 80 percent have gotten their diplomas and 40 percent have gone on to college. 60 percent remain in touch. Currently we run three programs that serve 60 students a year. Our Residential Program enrolls eight different students each winter and summer term. Mostly from Maine, these students and six teacher/counselors live at the School (the staff stays overnight in shifts) and study together for six months. The curriculum includes life skills, work skills and academics, as the students work at jobs in Camden or nearby towns. They perform cooking, cleaning, and other tasks for their shared household, and take classes and study in the evenings. Over 330 students have graduated from the Residential Program since its inception. Our Passages Program currently enrolls 24 teen parents, usually young moms, who are tutored in their homes by our teacher/counselors. To finish high school and get their diplomas, each student completes core skills in 23 areas with her one-to-one teacher, and then creates a “Walkabout,” a final independent project with the assistance of a team they assemble of friends, family members, peers, and people from the wider community. In the last five years, 41 students have graduated. Our Outreach Program further serves students and families who have participated in or graduated from the School. Through this program over 150 students a year contact the School (many are former Residential Program students with uncompleted course work), or use it for ongoing support, counseling, and to get help with job references and transcripts. Outreach also runs the intern program for prospective new teachers and counselors.

Relational Education is powerful. At the graduation of the summer-term students last September, we shared excerpts from a letter that alumni Ben McLaughlin had written to the graduating class:

“Attending and completing the semester at the Community School was one of the most positively influential experiences of my life,” he wrote. “The semester was by no means easy, but it was also never boring! I lived with seven other radical personalities that were not about to submit to any mold.We fought each other but we learned as well. Every one of us had something to offer the others but we were damned if they would get it for free. I want to thank all of you for the effort this endeavor has required. You are not quitters, you are not failures, you are a graduate of a true school of life.”

Several key values of Relational Education expressed in Ben’s letter–intimacy, connection, a sense of belonging, taking responsibility and respectful attention and trust–make Relational Education work. Several years ago I walked into a room where a new student, Eric, was taking a diagnostic test in English literature. He seemed agitated. Both feet were tapping nervously and he was sweating. Since he was an articulate young man I was surprised to find him so anxious, and asked him what was going on. He asked me why I was asking, and I explained what I was seeing. He admitted he was very nervous, and he had never passed a test in his life, so he was sure he would flunk this one. We talked at length, and I made sure that he knew his feelings were completely normal–why should he feel any other way? He let me know that the previous year he had been tested as having a third-grade reading level-but tested under the same circumstances of anxiety and paranoia. Over the next few days we all put a premium on helping Eric get calm by teaching him some relaxation methods, and assuring him that he would succeed. And he did. His reading went up seven grade levels in three weeks. To begin this learning experience however, Eric had to trust me–to open up, to explain to me what was going on with him–so that we could work together on a solution. The relationships with others that developed over his term helped to restore his confidence as a learner and as a competent human being. How readily can any of us assimilate information from someone we do not trust? How easy is it for us to learn in an environment we perceive as hostile, or inattentive? Relational Education proposes a shift in the role of teacher from conventional dispenser of knowledge to a listener, co-creator of knowledge, and facilitator. All Community School teachers work with “one to one’s”–specific students whom they advise throughout their stay at the School. We spend hours in meetings reflecting on and problem-solving individual situations as they arise with our students. We also regularly attend to our own interpersonal dynamics.

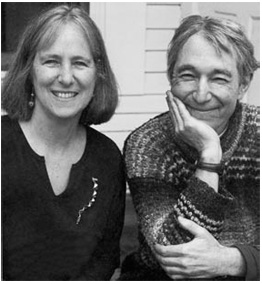

When Dora Lievow and I started the School in 1973, our teaching was based on a simple premise, which I wrote about in Changing Lives: Voices from a School that Works (University Press of America, 1994). “We wanted our students to enjoy life the way we did, and hoped that by using ourselves as models they would see the joy and value in the things we found important such as gardening, playing music, and discussing ideas, feelings, politics, philosophy, and psychology. We loved living and working with our students.” We also hoped to create an environment that was human scale–where interactions would not be driven primarily by individual roles as teacher and student, but by the essential qualities that make us human beings–our capacities to feel, to think, to imagine, and to empathize. We wanted other teachers to join our community with the same commitment to these values. We hoped that our students would use their graduation as a rite of passage into the adult world and they would become joyful, productive, creative adults. We soon began to experience the gap between our expectations and reality. Many students didn’t seem to want a voice in running the community. They ran afoul of alcohol and troublesome relationships, had difficulties breaking away from old friends who influenced them negatively, and were often angry and depressed. When we finally had the money to hire more staff, they generally didn’t seem to stay more than two years. We were stumped. What was wrong with 80-hour weeks at sub-dishwasher’s pay? Didn’t the rewards of community and teaching far outweigh the practical realities? Despite these initial disappointments we persevered and learned what worked. The School now has a successful track record and deep roots in the community and the state. Over 370 students have graduated. Of our 14 current staff members, three have worked with us for seven years and more, and one is entering his 21st year.

At Community School we believe teachers want to be treated and act like whole humans. They want to become part of a web of relationships that are ongoing and productive; they want to be supported and challenged as people. “When I first came to the Community School as an applicant for a teacher/counselor position I was immediately struck by the congeniality of the group. They seemed so ‘real’,” writes Eva O’Reilly. “The feeling of respect and genuine kindness was palpable. After working here for a year I still feel that. There is a focus on what is important in life: honesty, responsibility, respect, and a love for learning. The School allows me to teach in an authentic way, to begin to develop into the teacher I always wanted to be.”

Students must be treated as whole humans as well. “I arrived at the Community School in 1991 with a diminished trust in my peers, and virtually none in adults,” notes college junior Emma Hall. “After years as an A student in public school I began to experiment with drugs and lost interest in school fast. What was the most disturbing to me was that teachers and administrators seemed not to notice my drastic downfall, nor did they try to find out what was going on with me outside of school. Eventually they stopped asking for my homework or expecting anything from me at all. Some of them even stopped looking at me.” “I was 16 years old, and I wasn’t fitting into anything.” recalls Ed Foster, a 1980 graduate. “The School gave me a chance to fit in, a chance to succeed at something, a chance to be part of a community. At that age I needed a steady community, that sense of belonging–a steadiness within.”

The sense of community contributes to the learning here. This involves choice, trust, a sense of belonging, and taking responsibility. First of all, both students and teachers must choose to be here, developing a culture based on trust, openness, and belonging. Learning and teaching are difficult if not impossible when these qualities are absent. The reasons students choose the School range from wanting to finish high school and graduate to less obvious reasons such as getting out of an oppressive school, overcoming issues of mental health or substance abuse, or proving themselves to their families. Our teacher/counselors choose to work here despite low pay, long hours, and emotionally taxing experiences. “I can say what I think,” notes Passages director Lynne Witham. “I can be a real person with other students and staff. I get to work with people who really care about others.” “Here I have found that choice in what I teach and choice in what students learn can make all the difference in a lesson,” observes Ann Labonte. “I have had the most memorable teaching moments at times that I didn’t even realize I was teaching: walks with students, discussions or just listening. It’s not about standing up and preaching what I know, but being an open shelf students can take from or put something on.”

” Trust establishes the relationships that ultimately form the foundation of a sense of community. Residential students have a 24-hour community to immerse themselves in, with opportunities to develop trusting relationships with any of the eight adults who are regularly in their lives. But Passages students often live in isolated, temporary living situations. More than 60 percent have been abused as children or in their relationships, and trusting other people again is challenging. Our teachers come to their homes, work with them on core skills relevant to their lives, and spend a lot of time simply listening to their day-to-day issues. Trusting relationships develop over time, and, again, form the context for learning.

When students develop a sense of belonging within the School it bolsters the desire to achieve their goal of finishing high school. Although there are no grades for students in any of the programs, residential students are well aware of which students have completed what requirements, and they often use that knowledge to push themselves harder. Passages students, whose sense of belonging is fostered by one-to-one relationships with their teachers, have a chance to participate in monthly group workshops and connect with other students. Each Passage student’s Walkabout project involves assembling a committee made up of people important in their lives, such as friends, relatives, peers, and an “expert” in the area of their Passage. The chosen project must be of singular importance to the student, and involve some personal risk. One student who was afraid of driving chose learning to drive as her Passage project. She dealt with her anxiety and passed her learner’s exam. Another contacted a brother she had never met who had been adopted out of her family. These efforts become possible through a community of support for the students and in turn help strengthen the natural community students are a part of.

Students learn to take responsibility for themselves and care for others by being part of a community. “I had much more freedom at the Community School than I did at home,” notes Patty, a 1976 graduate. “But with freedom comes a certain responsibility–what you do not only affects yourself, but other people. How is what I do going to affect others?” Adolescents at the Community School have responsibilities that link them to other members of the community. Passages students must raise their children and manage a household; residential students must pay room and board, cook meals, and keep the house clean. The sense of interconnectedness these commitments foster can lead to a greater openness, respect, and understanding of others. “I was working with the elderly people up to the Camden Health Care Center, and that made me feel good–doing something for somebody else,” recalls Debbie, a 1990 student. “The School taught me responsibilities–work, keep up with chores, learn to budget your money.”

Relational Education also has its downside. Students and staff can find it hard to fit in. On average 20 percent of our residential students as well as Passages students leave without completing the term, or completing their Walkabout. Teacher/counselors stay only about three years. Dealing with personalities, conflicts, and power struggles demands emotional and intellectual stamina. As a staff we find it difficult to engage issues that seem to threaten our cohesiveness, knowing at the same time that not dealing with them also imperils our cohesiveness. As long as the School maintains a primary value on community and the relational, we will be troubleshooting these kinds of issues, person-by-person, and conflict-by-conflict. It’s not easy but, 28 years and 371 graduates later, we believe it’s well worth it.

Emanuel Pariser, who developed the theory of Relational Education, co-founded and co-directs the Community School, and co-authored the book Changing Lives: Voices from a School that Works. He has served for many years on state-level task forces and commissions and is on the steering committee of Maine’s Alternative Education Association.

Dora Lievow and Emauel Pariser, Co-Founders of The Community School